light body

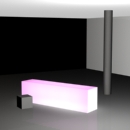

A Light Body is a large translucent three-dimensional architectural object, or element, such as a column, that is lit fully from within to produce a glowing light. A Light Body is not planar. more

light body | Light

research

Effects

A Light Body reveals light as a physically defined mass, thus emphasizing both mass and form of the object. A strong contrast with ambient light levels heightens its impact.1 The light of a Light Body is often low or balanced with other kinds of ambient illumination. The effect of light is often localized and attention is focused on the glowing object itself. Light Bodies are thus inefficient for task-oriented illumination and are seldom found in work areas.

When the contrast with surrounding light levels is high, light appears to emanate into space and activates the interior. A strong lighting contrast may begin to obscure form, but when the contrast is low, light appears contained and reserved. Most examples of Light Bodies are geometric forms with little ornamentation.

The diffuse light of fluorescent lamps was found to be an ideal medium for unobtrusively accentuating form. The solid Light Body presented light in an unconventional manner. Both fluorescent and neon lamps were commonly used for these new lighting applications.2

The arrangement of light sources may be revealed as light patterns on the surface of the Luminous Body, introducing a directional quality to the form. Uniform light levels across the entire surface results in an object or element being perceived as a single glowing entity; this technique effectively draws attention to the architectural form. (Fig. 1a) In practice, the concealed light sources are often seen on the translucent surfaces as brighter areas. Their shapes and arrangements affect the dynamic qualities of the planes; long shapes act like lines and direct energy along their length (Fig. 1b) or the gradient created by light (Fig. 1c); while point forms have a more static quality.3 (Fig. 1d) When multiple spots of appear on the plane, the luminous body is broken up into smaller sections, which, depending on the prominence of these brighter shapes, can compromise the appearance of the form as a whole.

Throughout the development of the practice, examples of evenly illuminated Light Bodies were matched by the same amount of those that were not.

Chronological Sequence

The Light Body practice may have its roots in the luminous architecture of the 1920 to 1930 eras in which buildings essentially became lanterns. Scheerbart's vision of luminous architecture in 1914 alluded to "many artificial lighting devices, including glowing columns that not only supported the building but also illuminated them".4 General Electric commissioned a report on the possibilities of luminous architectural elements in 1931, suggesting that luminous elements could replace any architectural element, such as "pylons, columns, pilasters, panels, parapets, spandrels; as beams, coves, coffers, moldings, niches, and decorative patterns..."5

Historically a Light Body as an interior lighting type can be documented in the 1970 decade, but its primary development occurred in the 1990 decade. Light Bodies are primarily found in the hospitality sector, as Dressed Columns, reception tables and bar counters in restaurants and hotel settings. The emergence of the new architectural lighting design profession in the 1960 period and a growing awareness about lighting as feature in itself gradually began to liberate designers from the quantitative mindset often held about interior lighting.

An early precedent of a Light Body was the floor-to-ceiling chandelier installed in the Patio restaurant (1972) in the Hess Department Store in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.6 The Venetian crystal emitted a local, non-directional glow and became the focal point of the space. Limiting the brightness of the structure to reduce glare simultaneously reduced the amount of light falling on surrounding surfaces.

A Light Body was often used as a focal object, or an element organizing space, such as the luminous column in the entertainment room of the Norfolk Airport Hilton Hotel (1988) and the bar at Odeum Karaoke Club in Tokyo (1992).7 In the dimmed environments of the lounge and the bar, a Light Body's soft glow emanates from a low light level to create an intimate atmosphere. Translucent panels were used to construct a solid form; the internal illumination relieved associations of weight in these large masses without compromising solidity. Thinly cut onyx and similar translucent stones were also used as an alternative to translucent glass or the various kinds of plastics. The integral color and texture or grain of natural materials proved more desirable in hospitality settings than the unflattering light of the more economical fluorescent sources.

Morphosis' office design for Friedland Jacobs Communication incorporated a thin long luminous block that penetrated through various rooms in the office.8 This Light Body provided both ambient lighting and task illumination for the work surfaces underneath it. It also became a large dramatic architectural feature.

The most striking examples of early Light Bodies were large, but reiterations at various scales began to appear through the 1990 decade as Light Body was embraced by new practice types, including residential and workplace design.

Light Bodies frequently served as featured objects s in large public spaces and helped way finding.

White LED was developed in 1995.9 Traditionally, a majority of lighting applications, including previous examples of Light Body were dominated by white light sources. It is therefore understandable that while ultra-bright LEDs were used in applications, such as electronic displays, its actual integration into architecture only developed toward the late 1990 decade. In addition to energy efficiency and color properties, the small size of LED gave them an advantage over fluorescent lamps in achieving even light distribution in more flexible configurations and smaller installations.

Some large Light Bodies occurred in public spaces, such as lobbies where they served as attractions, as well as organizing elements. In Tate Modern's (2000) west atrium entrance, luminous blocks emphasized the horizontal movement parallel to the skylights.10 The irregular-shaped luminous Wombi Rock in Mohegan Sun Casino's Casino of the Sky (2003) served as an anchor point that was simultaneously an entertainment facility on its own.11 Light added another level to the interior's compositional hierarchy and in examples such as the Tate Modern museum Light Body emphasized clean masses and lines over dashing colors, Light Body added subtle variations to the existing palette and differentiated the structure from its surroundings. The contained form of light injected an active, but controlled energy into the interior.

Several examples of Light Body appeared as doorframes and thresholds. For example, a glowing doorway at the W Hotel in New Orleans acted as a beacon for the entrance of the car park. The glowing Light Body also marked the transition between inside and outside.12

Luminous reception desks constitute some of the boldest statements of Light Body found across various practices. A clean, luminous reception desk created an excepting entrance without compromising a sense of professionalism desired by many firms. It was a part of Telenor's headquarters in Oslo, an "office-of-the-future" created by an international group of designers.13 The design firm II by IV used a Light Body for both the reception and the bar at Rain (2002).14 The elegant solid blocks of light appeared in striking contrast to the rings of small, round, sparkling "raindrops" of the chandeliers.

SANAA Architects' Dior Store in Tokyo appeared as a tower of light standing in the busy city. Likewise, its interior glowed from various luminous surfaces. The character in Dior was dependent on contrasting the even glow with other kinds of light. Light created a luminous white for the Black White interiors, amplifying the play of black and white that obscured depth and dematerialized the structures.15 In the perfume and cosmetics department, suspended white Light Bodies supported rotating polished steel makeup fixtures that juxtaposed sharp and darker reflections with diffuse white light from translucent panels. The Light Bodies guided the eye to a plain soft light, relieving the busyness created by the reflective finishes.

In the 2000 decade, various experimentations with the Light Body practice included: 1) textures revealed on luminous surfaces; 2) color components; 3) architectural integration using multiple modules. The soft vertical ellipse patterns on the vertical face of the bar at Rain produced a relatively stationary appearance. On the other hand, the more even glow across the nightclub's reception desk, and also Dior's luminous blocks seemed to emanate energy and expand in all directions.

In the 2000 to 2010 era, designers used larger continuous surfaces for Light Body reiterations. Reducing the structural frame lightened the visual weight of these the luminous bodies. In the most successful examples, the Light Body effect shifted from luminous objects towards pure solid light. In Vladmir Kagan's showroom in New York City, Light Body consisted of a frameless luminous plinth.16

While many examples of the Light Body continued to use white light sources, the growing range of colors offered by LEDs renewed interest in experimenting with colored light; Light Bodies employing color-changing technology were most frequently found in restaurants, bars and nightclubs where changing colors could vary the experience of the space. Colored lights were appreciated for their dramatic qualities appropriate for such venues, but the vibrant colors and color-changing effects also competed with a Light Body's form. The result was that color often became the dominating feature of the space. An article in Architectural Record characterized the color-changing-light feature as a gimmick, suggesting that designers use the technology with caution.17

At Morimoto in Philadelphia, PA, designer Karim Rashid distributed LED-lit glass half-partitions throughout the long space to create more intimate enclosure around tables. The LED lights continuously changed colors and intensified the luminous partitions, varying the restaurant's color palette throughout the night. The regularity and crisp forms of the colored partitions and the slow color-changes nonetheless resulted in "a more calming experience than you might expect."18

In response to the use of increasingly large luminous elements in the interior, luminaire designers also began to work more closely with architects, as well as produce fixtures that have become architectural in scale and shape, a gradual blurring of what is fixture and what is architecture. A good example is the Interface Flooring Showroom in Atlanta, Georgia.19 A massive drum-like Light Body pushes down from the ceiling plane to define a seating arrangement. This is an example where the design of lighting is so closely tied with an architectural element that it cannot be determined if the design began with architectural or lighting considerations.

The Light Body practice was used increasingly in the 2000 decade. With more energy efficient technology, such as LED, the practice of Light Body promises to continue unabated.20

end notes

- 1) Rudiger Ganslandt and Harald Hofmann, Handbook of Lighting Design (Ludenscheid, Germany: Erco, Leuchten GmbH, 1992), 39, 79. Large and relatively bright featureless luminous surfaces may cause a discomforting glare. "Discomfort glare occurs when an individual is involuntarily or unconsciously distracted by high luminance levels within the field of vision. The person's gaze is constantly being drawn away from the visual task to the glare source, although this area of increased brightness fails to provide the expected information." Discomfort glare is a problem that concerns the processing of information. An attraction of high luminence (brilliance) but offers no information content or obscures more important information becomes an unpleasant distraction. The handbook suggests an overcast sky and luminous ceilings to be conditions that may give rise to discomfort glare.

- 2) Intypes researcher Leah Scolere identified a Light Body in her 2004 retail study. She called it a Light Box, because of its use as a counter or display surface in retail design, noting that the primary light source was artificial and usually fluorescent. Leah Maureen Scolere, "Theory Studies: Contemporary Retail Design" (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2004), 32.

- 3) Francis D.K. Ching, Architecture, Form, Space & Order, 2nd ed. (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996), 4, 8-9.

- 4) Mark Major, Jonathan Speirs, Anthony Tischhauser, Made of Light: the Art of Light and Architecture (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2004), 39.

- 5) Dietrich Neumann, Architecture of the Night: the Illuminated Building (Munich, Germany: Prestel, 2002), 61, referencing Wentworth M. Potter and Phelps Meaker. "Luminous Architectural Elements." Transactions of the Illuminating Engineering Society 26, no. 10 (1931): 1025-1026.

- 6) Patio Restaurant [1972] Copeland, Novak & Israel; Hess Department Store; Lancaster, PA in Anonymous, "Luxury in Lancaster," Interior Design 43, no. 1 (Jan. 1972): 73; PhotoCrd: Henry S. Fullerton.

- 7) Entertainment Room, Norfolk Airport Hilton Hotel [1988] Ahearn-Schopfer and Associates; Norfolk, VA in John D. Coville, "Norfolk Airport Hilton," Interior Design 59, no.3 (Feb. 1988): 299; PhotoCrd: Peter Vanderwarker; Odeum Karaoke Club [1992] Totah Design; Tokyo, Japan in Mayer Rus, "Totah Design," Interior Design 63, no.16 (Dec. 1992): 105; PhotoCrd: Nacasa & Partners.

- 8) Art Department, Friedland Jacobs Communications [1997] Morphosis, archetects; X-Tec, lighting consultant; Santa Monica, CA in Edie Cohen, "Vision Quest," Interior Design 68, no. 4, (Mar. 1997): 130; PhotoCrd: Grant Mudford.

- 9) Tate Modern Museum [2000]; Adaptive Use, Bankside Power Station [1947]; Herzog & de Meuron, architect; Herzog & de Meuron with Office for Design, interior design; London, UK in William J.R. Curtis, "Herzog and de Meuron's Architecture of Luminosity and Transparency," Architectural Record 71, no. 6 (Jun. 2000): 102; PhotoCrd: Richard Bryant/Arcaid.

- 10) Wombi Rock and Slot Area, Mohegan Sun Casino [2002] KPF, architects; Rockwell Group, interior design; Fisher Marantz Stone, lighting consultant; Uncasville, CT in William Weathersby, Jr., "Rockwell Group guides Native American narratives into abstract territory at the Mohegan Sun casino," Architectural Record 190, no. 3 (Mar. 2002):187; PhotoCrd: Frederick Charles.

- 11) William Weathersby, Jr., "Rockwell Group Guides Native American Narratives into Abstract Territory at the Mohegan Sun Casino," Architectural Record 190, no. 3 (Mar. 2002):186-90.

- 12) Capark Entrance, W Hotel [2001]; Adaptive Use, Glass-and-Brick Hotel [1982]; Eskew+ and Powerstrip; New Orleans, LA in Abbey Bussel, "The Big W," Interior Design 72, no. 3 (Mar. 2001): S44; PhotoCrd: Neil Alexander.

- 13) Telenor Headquarters [2003] Joint Venture between NBBJ-HUS-PKA; Oslo, Norway in Peter MacKeith, "In a Joint Venture, NBBJ, HUS, and PKA Capture Precious Nordic Sunlight in a Dramatic Office Environment for Telenor's World Headquarters," Architectural Record 191, no. 5 (May 2003): 224; PhotoCrd: Tim Griffith.

- 14) Rain [2002] II by IV Design Associates; Toronto, Canada in Nayana Currimbhoy, "Dappled with Light, the Glossy Planes of Rain Frame an Evocative Setting for Tornoto Nightlife," Interior Design 73, no. 5 (May 2002): 308, 306; PhotoCrd: David Whittaker.

- 15) Dior Boutique [2004] SANAA, architect; Architecture & Associates, interior design; Tokyo, Japan in Ian Phillips, "Cities of Light," Interior Design 75, no. 4 (Apr. 2004): 162, 163,164; PhotoCrd: Jimmy Cohrssen.

- 16) Vladimir Kagan Showroom, New York Design Center [2008] Guigi Gentile; New York City, NY in Mark McMenamin, "Designwire: The Comeback Kid," Interior Design 79, no. 8 (Jun. 2008): 54; PhotoCrd: Vladimir Kagan Courtre Collection.

- 17) Morimoto [2002] Karim Rashid, designer; Focus Lighting, lighting consultants; Philadelphia, PA in Clifford A. Pearson, "Morimoto, Philadelphia," Architectural Record 190, no. 11 (Nov. 2002): 166; PhotoCrd: David Joseph/Snaps.

- 18) Pearson, "Morimoto," 166.

- 19) Interface Flooring Showroom [2005] TVS Interiors, designer; CDAI, lighting consultant; Fabmaster Inc., pendent fixture; Atlanta, GA in Stephen F. Milioti, "It Is Written," Interior Design 76, no. 8 (Jun. 2005): 114; PhotoCrd: Brian Gassel/ TVS&A.

- 20) Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Light Body was developed from the following primary sources: 1970 Patio Restaurant [1972] Copeland, Novak & Israel; Hess Department Store; Lancaster, PA in Anonymous, "Luxury in Lancaster," Interior Design 43, no. 1 (Jan. 1972): 73; PhotoCrd: Henry S. Fullerton / 1980 Entertainment Room, Norfolk Airport Hilton Hotel [1988] Ahearn-Schopfer and Associates; Norfolk, VA in John D. Coville, "Norfolk Airport Hilton," Interior Design 59, no.3 (Feb. 1988): 299; PhotoCrd: Peter Vanderwarker / 1990 Odeum Karaoke Club [1992] Totah Design; Tokyo, Japan in Mayer Rus, "Totah Design," Interior Design 63, no.16 (Dec. 1992): 105; PhotoCrd: Nacasa & Partners; Art Department, Friedland Jacobs Communications [1997] Morphosis, architects; X-Tec, lighting consultant; Santa Monica, CA in Edie Cohen, "Vision Quest," Interior Design 68, no. 4, (Mar. 1997): 130; PhotoCrd: Grant Mudford; Tate Modern Museum [2000]; Adaptive Use, Bankside Power Station [1947] / 2000 Herzog & de Meuron, architect; Herzog & de Meuron with Office for Design, interior design; London, UK in William J.R. Curtis, "Herzog and de Meuron's Architecture of Luminosity and Transparency," Architectural Record 71, no. 6 (Jun. 2000): 102; PhotoCrd: Richard Bryant/Arcaid; Wombi Rock and Slot Area, Mohegan Sun Casino [2002] KPF, architects; Rockwell Group, interior design; Fisher Marantz Stone, lighting consultant; Uncasville, CT in William Weathersby, Jr., "Rockwell Group Guides Native American Narratives into Abstract Territory at the Mohegan Sun Casino," Architectural Record 190, no. 3 (Mar. 2002):187; PhotoCrd: Frederick Charles; Capark Entrance, W Hotel [2001]; Adaptive Use, Glass-and-Brick Hotel [1982]; Eskew+ and Powerstrip; New Orleans, LA in Abbey Bussel, "The Big W," Interior Design 72, no. 3 (Mar. 2001): S44; PhotoCrd: Neil Alexander; Telenor Headquarters [2003] Joint Venture between NBBJ-HUS-PKA; Oslo, Norway in Peter MacKeith, "In a Joint Venture, NBBJ, HUS, and PKA Capture Precious Nordic Sunlight in a Dramatic Office Environment for Telenor's World Headquarters," Architectural Record 191, no. 5 (May 2003): 224; PhotoCrd: Tim Griffith; Rain [2002] II by IV Design Associates; Toronto, Canada in Nayana Currimbhoy, "Dappled with Light, the Glossy Planes of Rain Frame an Evocative Setting for Tornoto Nightlife," Interior Design 73, no. 5 (May 2002): 308, 306; PhotoCrd: David Whittaker; Dior Boutique [2004] SANAA, architect; Architecture & Associates, interior design; Tokyo, Japan in Ian Phillips, "Cities of Light," Interior Design 75, no. 4 (Apr. 2004): 162, 163,164; PhotoCrd: Jimmy Cohrssen; Vladimir Kagan Showroom, New York Design Center [2008] Guigi Gentile; New York City, NY in Mark McMenamin, "Designwire: The Comeback Kid," Interior Design 79, no. 8 (Jun. 2008): 54; PhotoCrd: Vladimir Kagan Courtre Collection); Morimoto [2002] Karim Rashid, designer; Focus Lighting, lighting consultants; Philadelphia, PA in Clifford A. Pearson, "Morimoto, Philadelphia," Architectural Record 190, no. 11 (Nov. 2002): 166; PhotoCrd: David Joseph/Snaps; Interface Flooring Showroom [2005] TVS Interiors, designer; CDAI, lighting consultant; Fabmaster Inc., pendent fixture; Atlanta, GA in Stephen F. Milioti, "It Is Written," Interior Design 76, no. 8 (Jun. 2005): 114; PhotoCrd: Brian Gassel/TVS&A.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) Kwan, Joanne. "Theory Studies: Archetypical Artificial Lighting Practices in Contemporary Interior Design." M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2009, 126-42.