Pompidou

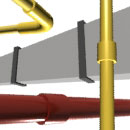

Pompidou, like its namesake building (Pompidou Center), intentionally exposes structural and mechanical systems in interior spaces. These elements are left in an original raw state, or painted, either uniformly a neutral color, or with certain ducts or pipes a bright accent color.

Pompidou | Workplace

application

In the workplace Pompidou is confined typically to an unfinished ceiling of exposed ducts, pipes, steel beams, pre-cast concrete tees or coffers and is typically used for adaptive use projects, as well as in smaller offices, circulation spaces, and public areas, such as cafeterias, where the absorption of noise is a low priority.

research

Ceilings are important factors in an office environment's ability to "provide services" and "can considerably affect the degree of flexibility of planning".1 Typical ceiling treatments in workplace environments include suspended ceilings, drywall, and plaster. There are numerous advantages and disadvantages of all three, but the general desired effect is to create a polished and orderly interior while concealing the structure of the building itself. Pompidou removes this layer of intervention, which "opens up a ceiling and adds a sense of sculpture".2 The curvilinear, interlacing forms of the ductwork draw interest and create change and variation on one major plane of the interior. The resulting aesthetic is that of an industrial space. Typical offices that demonstrate this Intype embrace a corporate culture that is more casual and unconstrained by the need for the rigidity and formality of finished ceilings. In the workplace Pompidou is rare in new construction projects. It is more commonly found in examples of adaptive use workplace environments that contrast a new interior with a pre-existing internal structure. In terms of sustainability, Pompidou replaces the customary and costly suspended ceiling. In 2010 Pompidou remained a commonly found strategy within offices whose work focuses primarily on the creative arts, because its inherent "unfinished" quality created an environment with few intrinsic behavioral rules.

Chronological Sequence

The workplace adaptation of Pompidou began in the 1970 decade when the Georges Pompidou Center (1971-1976) turned the architecture world upside down by celebrating the exposed skeleton of the mechanical system rather than concealing it within the structure. Originally the Pompidou systems were color coded according to function, but many of the bright tubes were painted white in the 2000 decade. Nevertheless, Pompidou also revolutionized workplaces transforming small offices and spaces within corporate offices.3

Early applications of Pompidou did not optimize the use of color in the ceiling, but rather treated the exposed structure in a uniform neutral color, sometimes leaving ductwork in its original aluminum state. The introduction of color treated exposed systems as artistic elements. Painted ducts or beams provided a "pop" of color, interjecting a sense of whimsy in the office, and furthering the impression of a low-keyed ambiance.

There is evidence that prior to the construction of Pompidou Centre an industrial aesthetic of the "raw state" of exposed pipes and systems was already underway in adaptive use and other preservation-driven projects. For example, the 1975 renovation of Ford & Earl's own New York City office, an adaptive use project, consisted of exposed beams and pipes were painted glossy white to complement the aluminum enclosures of air-conditioning ductwork. The project resulted in a juxtaposition of newly built gypsum walls contrasted with the exposure of the pre-existing ductwork above. The several reflective surfaces produced a sense of luminosity but did not disrupt the glare-free light level".4 Glossy white pipes and beams, along with unfinished aluminum ducts, softly reflected light emanating from fixtures dropped from the ceiling and illuminated the studio space.

In another example, Stanford University's 1978 office design project converted a former basketball arena into the Architecture and Planning Department's personnel workspace. The ceiling and steel structure were sprayed-off white to create a more polished aesthetic while still exposing and celebrating the original structure and the truss ceiling. Massive ducts were painted cardinal red, tying back to the University's official color with their "curves contrasting against the angular steel structure".5 This adaptive re-use project paid homage to the historical campus building by retaining its architectural integrity, but the project re-purposed the space for a dramatically different function.

Examples of Pompidou during the 1980 and 1990 decades were found in new construction projects rather than adaptive re-use. In the latter half of the 1980 decade when the dot-com boom emerged in California's Silicon Valley., new types of workplace campuses developed, particularly on the west coast where land was abundant. Office campuses offered a dramatic change from those within skyscrapers, as they were capable of large facilities for dining, recreation, and employee socialization spaced out over the landscaped site. As California companies expanded at extraordinarily fast rates to catch up with consumer demand, designers used the Pompidou treatment, because an interior could be finished quickly and efficiently.

This evolution ushered in a dramatic change in workplace culture. Corporate campuses fostered a casual work environment. Office culture was regarded as a life style in which Employees were given spaces and resources to explore their preferred work styles. Designers were charged with creating spaces that would optimize worker satisfaction.

Pompidou was implemented within corporate campuses as they often consisted of low, warehouse-like facilities whose interior was then subdivided into the various required spaces.6 Within these corporate campuses, Pompidou was found most prevalently in public spaces intended for socializing or interacting. Apple Inc. headquarters in Cupertino, California (1986) featured a brightly colored maze of ductwork woven into a structural framework. The impression was that of a play structure within the office setting.

In Silicon Graphics' Bay Area office/headquarters (1990) a Pompidou ceiling was featured in a common area utilized for dining and informal meetings. The ductwork, painted purple, created a sculptural element on the ceiling plane, while creating an informal setting for collaboration. The dining facility in the Caltran office in Marysville, California (2009) features ductwork in its original aluminum finish. Pompidou was an appropriate design strategy within these spaces, because the work culture promoted an environment of social interaction and a forum for employee communication.7

Between 2000 and 2010, the application of Pompidou was common and widespread. It remained popular within office renovations, such as that of the Holly Hunt Collection Design Studio (2001) in which the loft's "raw, industrial character" was celebrated while enabling the firm to cut down on the budget by nearly a half of what they would have paid for a more "polished" interior. At this point in Pompidou's evolution the exposed skeleton was no longer left in its original raw state, independent from the rest of the workplace. Pompidou, as an aesthetic, required thoughtful planning to incorporate it into the overall conceptual design of the space. In order to create a simple shell, the architects for Holly Hunt "worked hard to clean up" the skeleton, leaving only beams and pipes whose rhythm "guided the division of space and gave way to natural niches".8 Columns, beams, and slabs were sandblasted prior to construction to further create a sense of texture, contrast, and unity within the interior.

The 2000 to 2010 period also brought about the widespread application of Pompidou in Asian countries. With the influence of western design in Asia, many workplaces adopted the "warehouse aesthetic" of Pompidou, a tremendous change from traditional Eastern design practice. In contemporary Asian workplace design, Pompidou was finished with all-white paint to create a White Box or White-Out interior. In the On Media office (2008) in South Korea, Pompidou was utilized throughout the space and finished uniformly in a natural white color.9 In Saatchi & Saatchi in Beijing, a large conference space incorporated Pompidou as part of a White Out interior in which the ceiling and wall planes disappear.10

end notes

- 1) John Pile, Open Office Planning (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1978), 109-19.

- 2) Roger Yee, Corporate Design (New York: Interior Design Books, 1983), 216.

- 3) For a 19th century history leading to Pompidou, see the Intype Pompidou | Material http://www.intypes.cornell.edu/expanded.cfm?erID=114

- 4) Ford & Earl Design Associates Office [1975] Ford & Earl Design Associates; New York City in Anonymous, "Planned Economy," Interior Design 46, no. 4 (Apr. 1975): 147; PhotoCrd: Carmine Bilardello.

- 5) Stanford University Architecture Department Personnel Offices [1978] Barry Brukoff; San Francisco, CA in Anonymous, "Open Planning in Sheer Space," Interior Design 49, no. 5 (May 1978): 205; PhotoCrd: Jeremiah O. Bergstad.

- 6) James S. Russell, "Form Follows Fad," On the Job: Design and the American Office, ed. Donald Albrecht (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000), 60.

- 7) Silicon Graphics [1990] Studios Architecture; San Francisco, CA in Edie Cohen, "Silicon Graphics," Interior Design 61, no. 6 (Apr. 1990): 171; PhotoCrd: Paul Warchol.

- 8) Holly Hunt [2001] Piotrowski + Ecker; Great Plains, NY in Julia Lewis, "Warehouse Proud," Interior Design 72, no. 5 (May 2001): 290; PhotoCrd: Jon Miller, Hedrich-Blessing.

- 9) On Media [2008] Heehoon D&G; South Korea in Anonymous, "Heehoon D&G," Interior Design 79, no. 7 (May 2008): 326; PhotoCrd: Lee Soonshim; Saatchi & Saatchi [2009] Red House China; Beijing, China in Aric Chen, "Shout It Out," Interior Design 80, no. 7 (May-2009): 205; PhotoCrd: Zhiyi Zhou.

- 10) Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Pompidou in workplace design was developed from the following primary sources: 1970 Ford & Earl Design Associates Office [1975] Ford & Earl Design Associates; New York City in Anonymous, "Planned Economy," Interior Design 46, no. 4 (Apr. 1975): 147; PhotoCrd: Carmine Bilardello; Stanford University Architecture Department Personnel Offices [1978] Barry Brukoff; San Francisco, CA in Anonymous, "Open Planning in Sheer Space," Interior Design 49, no. 5 (May 1978): 205; PhotoCrd: Jeremiah O. Bergstad; James S. Russell, "Form Follows Fad," On the Job: Design and the American Office, ed. Donald Albrecht (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000), 60 / 1990 Silicon Graphics [1990] Studios Architecture; San Francisco, CA in Edie Cohen, "Silicon Graphics," Interior Design 61, no. 6 (Apr. 1990): 171; PhotoCrd: Paul Warchol / 2000 Holly Hunt [2001] Piotrowski + Ecker; Great Plains, NY in Julia Lewis, "Warehouse Proud," Interior Design 72, no. 5 (May 2001): 290; PhotoCrd: Jon Miller, Hedrich-Blessing; On Media [2008] Heehoon D&G; South Korea in Anonymous, "Heehoon D&G," Interior Design 79, no. 7 (May 2008): 326; PhotoCrd: Lee Soonshim; Saatchi & Saatchi [2009] Red House China; Beijing, China in Aric Chen, "Shout It Out," Interior Design 80, no. 7 (May-2009): 205; PhotoCrd: Zhiyi Zhou.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) Yin, Shuqing. "Theory Studies: Archetypical Workplace Practices in Contemporary Interior Design." M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2011, 182-95.