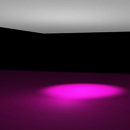

Hotspot

Hotspot is an isolated pool of bright downlight that operates in contrast to its surroundings. Hotspot encourages a pause in movement and collection around or within it. It is achieved with a single spot light or a single fixture on a light track. more

Hotspot | Showroom

application

In furniture, furnishings and automobile showrooms Hotspot appears in multiples as a spatial, lighting and display strategy. Hotspot is usually used in lieu of any other display unit or mechanism, and is frequently implemented in large, open plan showrooms that have little or no spatial partitioning of the interior.

research

In showrooms, Hotspot creates three spatial, lighting, and display effects. The first is a macro effect in which multiple pools of light organize space by creating several foci of displayed merchandise. This effect pulls together diverse elements and facilitates seeing the whole spatial scheme. In the second effect, the emphasis is on multiple objects in space. Multiple objects stand out in contrast to their surroundings. This effect separates important objects, the merchandise, from the unimportant. The third is a micro effect in which Hotspot isolates an individual object as a zone of light that implies a Vitrine,1 suggesting that the object contained within is of great worth, as if it were an art object.

Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Hotspot in the showroom practice type was developed from site visits to the Boston Design Center and various New York City showrooms in March 2011, and car showrooms in Munich and Stuttgart in may 2011, as well as from published trade sources, including Interior Design, Architectural Record, and Interiors magazine.

Hotspot can be used instead of the display practices Plinth2 or Vitrine to draw attention to and elevate the status of products on display. It can also used instead of interior partitions as a means of separating different vignettes from one another. In some installations, the pools of light are more accurately described as an expression of Follow Me3, directing the flow of circulation around the showroom floor.4 In these instances, products may still be highlighted, but these will be incidental to the circulation path defined by the pools of light.5

The precursor to the Hotspot archetype is the campfire, the most basic embodiment of artificial light. It was created out of a necessity to "illuminate our world after dark," both to continue working and also to be able to see any hidden dangers in the nighttime void. The single source of light that stands out from the darkness has strong cultural associations for all humans. It is historically not only a source of light, but also of warmth, "security, power and ritual."6

Humans are instinctively attracted to light. It is an evolutionary instinct stemming from a time when sunlight or fire meant warmth and safety above all else. Being attracted to a point of light in the darkness meant that primitive humans could find a clearing in a dark forest, or a campfire in the dark. The latter often meant safety and security, as a campfire could also imply food and other people to help fight off any nighttime predators. This primal attraction to light is so powerful that, as Marietta S. Millet explains, light alone is often enough to "beckon us down a path, through the woods to open fields, to the end of a tunnel,"7 although we have no idea what might lie there. Our primal instincts urge us on, because of an innate belief that light is better than what hides in the dark. The contrast of light and dark implies an inside and an outside - a zone of safety and a zone of danger.

As humans evolved, light began to be used in conjunction with architecture. At first, there was no real strategy involved; in most cultures, the earliest buildings were created solely as a means of shelter. Because most people spent their time outdoors during daylight hours, there was no real need to light interior spaces. Any openings in the envelope of the structure were made primarily for access or ventilation, rather than for the penetration of daylight- not to mention the fact that most openings would also have the unwanted side effect of letting in the weather.8

The earliest manipulations of lighting within a structure often occurred in religious or sacred spaces. Ancient cultures "employed celestial bodies as a source for layout and design," and the atmosphere created by the light was meant to be symbolic of their religious or cultural values.9 Although these effects were largely created with natural daylight, they were preserved when artificial lighting became the dominant method for lighting interior architecture.

In terms of artificial lighting strategy, Hotspot is the embodiment of what Richard Kelly defines as "focal glow," "the campfire of all time," and the "follow spot on the modern stage." It "draws attention, pulls together diverse parts, sells merchandise, separates the important from the unimportant, helps people see." Focal glow plays upon humans' intrinsic attraction to light to attract the eye to move from one area to another. If multiple foci occur, then the lighting composition becomes more complex as a pattern of light and dark draws the eye from one area to another. Too many areas of focal glow, however, can become ambient luminescence-or a graded wash of light, which emphasizes nothing. Hotspot also contributes to the overall lighting effect. Because the source of the light pool necessarily comes from above eye-level, a formal atmosphere is created. However, since the pools of light occur on the ground plane, the light pools fall below eye-level, creating a "feeling of individual importance."10

As a display strategy, Hotspot draws attention to the product or products placed within it. By bathing the object in a pool of light, an object stands out from its comparatively darker surroundings. This highlight effect bestows importance upon the object, subtly indicating to the viewer that the object is worthy of attention. Because the object is effectively "inside" a pool of light, the Hotspot also implies a separate volume of space reminiscent of a Vitrine. The more clearly defined the edge of the Hotspot is, the stronger the boundary is implied. Objects within sharp-edged Hotspots seem more important and intangible than those within washes of light. This boundary is only implied, however, and patrons are in fact free to touch and interact with the object.

Hotspot also visually breaks up large, open spaces. Because "light can define distinctly different places within a large area,"11 the pools of light created by Hotspots are perceived as distinct, but separate areas. This allows large, open plan showrooms to use only light as a means of partitioning the space, enabling visitors to quickly see all merchandise on display. The showroom is perceived as having many, smaller areas within it, but the entire space remains as visually accessible as possible.

Hotspot adds a sense of drama to displays, creating an atmosphere that is otherwise lacking in showrooms lit only with ambient light. In Exhibition Techniques, James H. Carmel states that "A dark room with individually lighted objects enhances the dramatic appeal"12 of an exhibit. The dramatic atmosphere may be a vestige of our primal attraction to light, or it may be a more recent callback to the limelight spots used to highlight performers on stage. Either way, the tension created by the contrast of light and dark within the space is often enough to subtly suggest to patrons that the merchandise is important and exciting.

The patterns created by Hotspots on the showroom floor can be separated into two different spatial organization categories. In its pure form, Hotspot creates a single pool of light on the showroom floor. Placed against the contrasting visual field of the rest of the showroom, this disc of light acts as a single point in space and is therefore "static, centralized, and directionless." If the Hotspot occurs in the center of the showroom, it acts as a point of stability, "dominating its field." Circulation paths and secondary displays are organized around it, making it the strongest focal point in the entire space. If the single pool of light is noticeably off-center, "its field becomes aggressive and begins to compete for visual supremacy,"13 because tension is created between the point of light and the comparatively darker showroom floor. This particular manifestation of Hotspot is not popular in the showroom practice type because it draws attention to only one object or display of objects on the showroom floor.

The most popular form of Hotspot creates multiple pools of light, which stand out against the rest of the showroom. These Hotspots are most commonly found in a clustered organization, which according to architect Francis Ching, "relies on physical proximity to relate its spaces to one another." This means that the repetitive, cell-like spaces can "accept within [their] composition spaces that are dissimilar in size, form, and function." This strategy allows maximum flexibility for showroom displays because the pools of light and the objects contained within them can vary in size, shape and color and yet still seem related to the other Hotspots around the showroom. It also allows for products to be easily moved or rearranged, as the clustered organization doesn't adhere to any rigid geometrical ordering principles and thus "can accept growth and change readily" without affecting the character of the showroom. The clustered organization also solves the problem of hierarchy by creating a single point Hotspot strategy. By having multiple Hotspots of differing sizes scattered around the showroom floor, "there is no inherent place of importance"14 within the pattern of displays. Instead, any intended hierarchy within the pattern of Hotspots must be intentionally made through size, form, or placement within the showroom.

Chronological Sequence

Decade of 1950

Although many contemporary showrooms emulate the aesthetics and sensibilities of empty, reverent White Box museum and gallery spaces, in the 1950 decade the model was decidedly residential. Architect James C. Morse designed the 1959 Tomlinson Showroom in High Point, North Carolina to display a single collection of the furniture manufacturer-the new Pavane line. Morse set the collection in a residential installation to demonstrate how the various pieces could be arranged into various groupings that felt integrated "but without the usual ‘one manufacturer' look."15 The only non-residential variant was lighting. Although various table lamps added to the showroom's overall homelike quality, Hotspots distinguished various pieces of the collection, making it clear that these pieces were on display.

Decade of 1960

By the decade of 1960, showrooms had started to adopt the museum-like characteristics that contemporary showrooms embody today. Designed in 1965 by Brickel-Eppinger Inc., the Ward Bennett showroom was far different than the Tomlinson showroom of six years earlier. For one thing, the showroom had that empty openness that is so reminiscent of gallery spaces; furniture pieces floated free in space. Partitions within the showroom were not full height, and the ceiling was painted black to hide exposed pipes and structural beams. The furniture was not arranged in homey vignettes, but rather in displays, which were housed in niches. Additionally, a "changing exhibit of art" was displayed among the furniture, blurring the line between showroom and gallery. To add further drama to the space, "Edison Price spots with special lens and early theatrical fixtures,"16 were used to light each of the displays in the space. The effect was that each display was isolated not only in its own niche, but also within its own Hotspot, reverently highlighting it within the darkened showroom.

The 1966 Jack Lenor Larsen showroom took a similar approach. Jointly designed by Larsen and Charles Forberg, the showroom was intended to be original and slightly dramatic. To achieve this effect, structural fabric shaped into "kite-shaped panels" was stretched across the ceiling to hide pipes while "creating an intriguing pattern." In between the panels, a variety of spotlights "highlight[ed] displays of fabrics and arts and crafts." Indeed, the spotlights created a wall-wash effect on textiles hung on the vertical surfaces, as well as pools of light around furniture and objects arranged on the showroom floor. The space itself was windowless; artificial lighting produced the only light in the showroom. The effect was meant to be "soft and pleasing to the eye" by creating a "somewhat romantic mood." It remained, however, "eminently practical"17 as the Hotspots succeeded in drawing attention to the merchandise for sale.

Decade of 1970

By the 1970s, Hotspot had become a common design strategy in the showroom repertoire; it varied little in execution. The 1976 Knoll showroom at the Pacific Design Center provides a quintessential example of how Hotspot is generally implemented in showrooms. The showroom space itself was expansive, windowless and wide-open. Designer Cini Boeri preserved these qualities by foregoing vertical partitions to divide the space. Instead, she designed a terraced floor with each level carpeted in "variations of a single color"- pink, in this case. To give some presence to the furniture groupings in the partition-less space, pieces were spotlighted, so that each little display was anchored in a pool of light. The showroom was subtle and simple- fitting, since Boeri was instructed to "build a background" rather than a "masterpiece."18 Fittingly, the showroom acted as no more than a stage for the various furniture pieces on display. Although the terraced floor broke the space into smaller, more human-scaled areas, the Hotspots drew attention to the merchandise, effectively making the pieces the focal points of the space.

The 1980 Knoll Showroom by Robert Venturi is a slightly more florid take on its 1976 cousin. It is a product of the two schools of thought that were polarizing showroom design at the time: "One treats the space as a stage where dramatic exhibits often rival products for focus of attention. The other favors a pristine background where little upstages the products for sale." More often than not, Hotspot is used in the latter school of thought as a way of drawing attention to the merchandise in the least invasive manner possible. Venturi combined both approaches in the Knoll space. On the side of outlandish displays, he created a dramatic "waterfall of fabrics, mostly velvets in deep tones" that spanned the void from the first floor to the second floor. He also created a colorful "trompe l'oeil fabric display wall" that mimicked a real one further back in the showroom. On the side of simplicity, the showroom itself was devoid of partitions, containing only fat structural columns and furniture. The color, too, was subdued; a light beige adorned the walls, while taupe carpeting subtly delineated the floor plane. Furniture was arranged into small groupings suggesting how one might use the pieces. Hotspots drew attention to the groupings, creating "organized clutter." The aim of the space was to encourage visitors to "sit in, walk around and move individual pieces without fear of disturbing a structured display."19 However, the pools of light also suggested the display zones, encouraging visitors to put the pieces back when they were done.

By the late 1980s, designers had become more creative with their implementation of Hotspot. While previous showrooms had employed the Intype in almost identical ways, showroom designers of the late 1980s and early 1990s did not hesitate in experimenting with the effects of Hotspot's focal glow. The 1987 showroom for the Metropolitan Furniture Corporation used Hotspot in conjunction with the space's architectural features. Designer Mark Kapta created a colonnade in the entry20 of structural columns that could not be altered. A chair and a spotlight was aligned with each column to produce a Marching Order.21 Hotspots enhanced the visual rhythm and regulated the speed of movement into the space. As the Hotspots drew attention to the individual chairs on display, the repetitive sequence of the light pools suggested a line, beckoning a visitor down the path.22 In this instance, Hotspots also constituted the circulation and lighting Intype Follow Me-sequenced pools of light on the floor that are in contrast with the surrounding space, defining a circulation path.

Decade of 1980

The 1989 Lackawanna Leather showroom was similarly creative with the implementation of Hotspot. Designers Andrew Belschner and Joseph Vincent wanted the showroom to "put on a theatrical performance," dramatizing the "many uses of leather" and encouraging the visitors to touch the product. In the largest area in the showroom, they displayed leather that was reminiscent of a group of ballet dancers. Strips of leather different colored leather were cut to three lengths and hung from metal rods. The rods were attached to individual motors that let the fabric "sway and swirl" to "other-worldly electronic music" as if "stirred by a gentle breeze." Over each piece of fabric was a small spotlight, highlighting the colorful strips in their own individual Hotspots. On the floor, galvanized metal plates sparkled as the moving fabric interacted with the spotlights.23 Interestingly, the close proximity of the spotlights to one another also gave the effect of one, giant Hotspot on the showroom floor, exaggerating the effect of "focal glow".

Decade of 1990

Previous showroom installations adopted Hotspot as a product-emphasizing technique within a spacious, open-plan showroom, but in the Los Angeles showroom of Bernhardt (1990), such an open space-plan was not an option. Neither was it an option to arrange the furniture into the little vignettes typical of showrooms, because the space was long and narrow, measuring only seventy one-feet four-inches deep and nineteen-feet six inches wide. Instead, Vanderbyl Design split the long corridor-like space into a "series of anterooms" that ran the length of the space.24 Pieces of furniture were casually arranged in each of these anterooms, although not close enough to each other to constitute a vignette. Spotlights were then focused on each piece of furniture. The effect drew attention to the pieces, which also made their arrangement seem less haphazard. The practice of Hotspot worked to ground the displays, making them seem purposeful within the small space.

Designer Tom Gass reinterpreted Hotspot by abstracting it for the United Chair showroom (1991) in Chicago. Gass intended to draw visitors inside with a black and white carpet on the main showroom floor. Once inside the entrance, a carpet inset reminiscent of a zebra crossing was designed to draw visitors to the other end of the showroom. The main focus of the showroom, however, was a chair display on the left of the patrons as they moved through the space. Six tidy groupings, composed of four red chairs arranged about a small, round table, created the main exhibit of chairs. Above each chair and table was a spotlight; under each chair, the black carpet was punctuated with a three-foot diameter circular insert of a cream-colored carpet.25 The Hotspot effect emphasized the chairs, creating an obvious lighter circle where the effect might have been diluted in the black carpeting. The cream colored circles, created by Hotspot, provided a point of focus, drawing attention to the chairs through their contrast to the surrounding environment. At the same time, Hotspot acted as an organizational mechanism, discouraging patrons from moving the chairs from their designated cells.

Decade of 2000

By the decade of 2000, the philosophical argument between designers who thought showrooms should consist of dramatic exhibits and those who believed in simple, clean backgrounds had largely extinguished, as designers and architects on the whole began to prefer cleaner, simpler design solutions. The Wilson Sporting Goods showroom (2007) by Gensler resembled a museum gallery; there was nothing at all to distract one's attention from the objects on display.26 A separate sports item was displayed on a Plinth (Intype) and lit with a Hotspot, as if denoting an objet d'art.27 Like a gallery setting, this composition encouraged visitors to look at and to circulate around the displays, but not to touch.

The Tesla Motors showroom (2009) in Los Angeles reiterated the showroom-as-gallery concept. This design strategy is popular with car showrooms, primarily because the size of an automobile disallows it to be displayed in a vignette. Tesla's gallery of one car with a large space around it was an intentional contrast to typical car showrooms, which crowded cars on the floor. Designer Cass Calder Smith reasoned that the electric car did not "need a lot of stuff around to sell it," so the flagship space was kept empty and aesthetically raw with concrete floors, exposed ceiling trusses (Pompidou) and white walls (White Box).28 Each car was bathed in a Hotspot, neatly highlighting it within the darkened interior. However, in this case, the artificial light had the added side-effect of making the pristine surfaces of the cars sparkle and gleam. The lighting not only evoked reverence from patrons, but also romanticized the car, subtly encouraging visitors to make a purchase.

Although Hotspot is one the oldest showroom interior archetypes, it is also one of the most consistent, because lighting and organizational strategies disallow much room for abstraction or re-interpretation. It shows no sign of abatement as a showroom strategy. In terms of energy conservation, the only variation in Hotspot's future may be the type of lamp used.29

end notes

- 1) The Intype Vitrine describes a glass showcase for the display of significant or ordinary objects. Kristin Malyak, "Theory Studies: Archetypical Retail Practices in Contemporary Interior Design" (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2011), 232-95; The Interior Archetype Research and Teaching Project, http://www.intypes.cornell.edu/intypesub.cfm?inTypeID=126 (accessed Oct. 12, 2011).

- 2) The Intype Plinth describes a platform (usually one step) that elevates an object slightly off the floor. Courtney Cheng, "Theory Studies: Archetypical Showroom Practices in Contemporary Interior Design," (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2012), 113-59; The Interior Archetype Research and Teaching Project.

- 3) The Intype Follow Me describes sequenced pools of light on the floor that are in contrast with the surrounding space, defining a circulation path. Joanne Kwan, "Theory Studies: Archetypical Artificial Lighting Practices in Contemporary Interior Design" (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2009), 52-66; The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, http://www.intypes.cornell.edu/expanded.cfm?erID=163 (accessed Oct. 12, 2011).

- 4) Ward Bennett Showroom [1959] Charles F. Murray, architect; New York City in Anonymous, "Showrooms," Interior Design 30, no. 10 (Oct. 1959): 219; PhotoCrd: Anonymous; Haworth Showroom [1986] Wyatt Stapper Architects, architect; Seattle, WA in Monica Geran, "Haworth, Seattle," Interior Design 57, no. 7 (Jul. 1986): 230-33; PhotoCrd: Robert Pisano.

- 5) United Chair Showroom [1993] Tom Gass, architect; Washington, D.C. in Monica Geran, "Tom Gass," Interior Design 64, no. 1 (Jan. 1993): 142-45; PhotoCrd: Peter Paige.

- 6) Mark Major, Jonathan Speirs, and Anthon Tischhauser, Made of Light: The Art of Light and Architecture (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2004), 13; Major, Made of Light, 18.

- 7) Marietta S. Millet, Light Revealing Architecture (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996), 118.

- 8) Major, Speirs and Tischhauser, Made of Light, 25.

- 9) Major, Speirs and Tischhauser, Made of Light, 25.

- 10) Richard Kelly, "Lighting as an Integral Part of Architecture," College Art Journal 12, no. 1 (Autumn, 1952): 24-30.

- 11) Millet, Light Revealing, 110.

- 12) James H. Carmel, Exhibition Techniques, Travelling and Temporary (New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1962), 119.

- 13) Francis D.K. Ching, Architecture: Form, Space & Order, 2nd Ed, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996), 4-5.

- 14) Ching, Architecture: Form, Space & Order, 214.

- 15) Tomlinson Showroom [1959] James C. Morse, architect; High Point, NC in Anonymous, "Showrooms," Interior Design 30, no. 10 (Oct. 1959): 217; PhotoCrd: Anonymous.

- 16) Ward Bennett Showroom [1965] Brickel-Eppinger, Inc., architect; New York City in Anonymous, "Showrooms: Brickel-Eppinger," Interior Design 36, no. 1 (Jan. 1965): 128-29; PhotoCrd: Jon Naar.

- 17) Jack Larsen Showroom [1966] Charles Forber, architect; Jack Larsen, designer; New York City in Anonymous, "High, Wide and Handsome," Interior Design 37, no. 9 (Sep. 1966): 188-91; PhotoCrd: James Vincent.

- 18) Knoll Showroom [1976] Cini Boeri, architect; Los Angeles, CA in Anonymous, "Knoll in the Pacific Design Center," Interior Design 47, no. 7 (Jul. 1976): 78-79; PhotoCrd: Darwin Davidson.

- 19) Knoll Showroom [1980] Robert Venturi, architect; New York City in E.C., "Complexity and Contradiction," Interior Design 51, no. 3 (Mar. 1980): 226-30; PhotoCrd: Tom Crane.

- 20) Metropolitan Furniture Corporation Showroom [1987] Mark Kapka, architect; Chicago, IL in Monica Geran, "Metropolitan Furniture Corp.," Interior Design 58, no. 15 (Dec. 1987): 190-93; PhotoCrd: Steven Blutter.

- 21) The Intype Marching Order describes a sequence of repeating forms organized consecutively, one after another. It establishes a measured spatial order. Marching Order constitutes a chapter of this thesis, because it is a strategic practice of showroom design. Marching Order has also been identified as a design practice in Retail and Workplace. The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, http://www.intypes.cornell.edu/intypesub.cfm?inTypeID=95 (accessed Oct. 12, 2011).

- 22) Joanne Pui Yuk Kwan, "Theory Studies: Archetypical Artificial Lighting Practices in Contemporary Interior Design" (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2010), 52-66.

- 23) Lackawanna Leather Showroom [1989] Andrew Belschner & Joseph Vincent, architects; Chicago, IL in Monica Geran, "Lackawanna Leather," Interior Design 60, no. 16 (Dec. 1989): 132-35; PhotoCrd: Hedrich-Blessing.

- 24) Bernhardt Showroom [1990] Vanderbyl Design, architect; Los Angeles, CA in Judith Nasatir, "Bernhardt, Los Angeles," Interior Design 61, no. 2 (Feb. 1990): 230-33; PhotoCrd: Sharon Risedorph.

- 25) United Chair Showroom [1991] Tom Gass, architect; Chicago, IL in Monica Geran, "United Chair," Interior Design 62, no. 14 (Oct. 1991): 172-75; PhotoCrd: Hedrich-Blessing.

- 26) Wilson Sporting Goods Showroom [2007] Gensler, architect; Chicago, IL in Deborah Wilk, "Best of Year: Showroom," Interior Design 78, no. 15 (Dec. 2007): 84; PhotoCrd: Hedrich-Blessing.

- 27) Tesla Motors Showroom [2009] Cass Calder Smith, architect; Los Angeles, CA in Edie Cohen, "Hot Rods, Cool Digs," Interior Design 80, no. 3 (Mar. 2009): 63-64, 66; PhotoCrd: Eric Laignel.

- 28) Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Hotspot in the showroom practice type was developed from site visits to the Boston Design Center and various New York City showrooms in March 2011, and car showrooms in Munich and Stuttgart in May 2011, as well as from the following print sources: 1950 Tomlinson Showroom [1959] James C. Morse, architect; High Point, NC in Anonymous, "Showrooms," Interior Design 30, no. 10 (Oct. 1959): 217; PhotoCrd: Anonymous; / 1960 Ward Bennett Showroom [1965] Brickel-Eppinger, Inc., architect; New York City in Anonymous, "Showrooms: Brickel-Eppinger," Interior Design 36, no. 1 (Jan. 1965): 128-129; PhotoCrd: Jon Naar; Jack Larsen Showroom [1966] Charles Forberg & Jack Larsen, architects; New York City in Anonymous, "High, Wide and Handsome," Interior Design 37, no. 9 (Sep. 1966): 188-191; PhotoCrd: James Vincent; / 1970 Knoll Showroom [1976] Cini Boeri, architect; Los Angeles, CA in Anonymous, "Knoll in the Pacific Design Center," Interior Design 47, no. 7 (Jul. 1976): 78-79; PhotoCrd: Darwin Davidson; / 1980 Knoll Showroom [1980] Robert Venturi, architect; New York City in E.C., "Complexity and Contradiction," Interior Design 51, no. 3 (Mar. 1980): 226-230; PhotoCrd: Tom Crane; Metropolitan Furniture Corporation Showroom [1987] Mark Kapka, architect; Chicago, IL in Monica Geran, "Metropolitan Furniture Corp.," Interior Design 58, no. 12? (Dec. 1987): 190-193; PhotoCrd: Steven Blutter; Lackawanna Leather Showroom [1989] Andrew Belschner & Joseph Vincent, architects; Chicago, IL in Monica Geran, "Lackawanna Leather," Interior Design 60, no. 12? (Dec. 1989): 132-135; PhotoCrd: Hedrich-Blessing; / 1990 Bernhardt Showroom [1990] Vanderbyl Design, architect; Los Angeles, CA in Judith Nasatir, "Bernhardt, Los Angeles," Interior Design 61, no. 2 (Feb. 1990): 230-233; PhotoCrd: Sharon Risedorph; United Chair Showroom [1991] Tom Gass, architect; Chicago, IL in Monica Geran, "United Chair," Interior Design 62, no. 10? (Oct. 1991): 172-175; PhotoCrd: Hedrich-Blessing; / 2000 Wilson Sporting Goods Showroom [2007] Gensler, architect; Chicago, IL in Deborah Wilk, "Best of Year: Showroom," Interior Design 78, no. 15 (Dec. 2007): 84; PhotoCrd: Hedrich-Blessing; Tesla Motors Showroom [2009] Cass Calder Smith, architect; Los Angeles, CA in Edie Cohen, "Hot Rods, Cool Digs," Interior Design 80, no. 3 (Mar. 2009): 63-64, 66; PhotoCrd: Eric Laignel.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) Courtney Cheng, "Theory Studies: Archetypical Showroom Practices in Contemporary Interior Design" (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2012), 91-112.