Camouflage

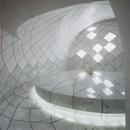

Camouflage refers to the application of a consistent pattern to the wall, floor, and ceiling planes, as well as furnishings. Wrapping the interior with a continuous pattern effectively blurs the transition between horizontal and vertical planes or between planes and furnishings. more

Camouflage | Resort & Spa

application

Resorts and spas utilize tile as Camouflage as a strategy for positive distraction, a vehicle for mentally transporting the guest.

research

Camouflage, as explained by Elizabeth O’Brien in her archetypical study of materials, began in art galleries as an exploration of the “relative interactions between site, object, and viewer.”1 As a material application, O’Brien asserts that Camouflage originated with the Minimalist work of Frank Stella and other installation artists of the 1960s and 1970s, but it is the installation art of the late 1970s and 1980s that show a direct correlation between art galleries and the employment of Camouflage in resort and spa interiors.

Daniel Tremblay used Camouflage in “The Lost Wave” (1984) to impart a specific effect, an interaction between viewer perception and an enveloping environment, as he “transformed the Museum’s ocean-view gallery with thousands of postcard views of La Jolla’s beaches, …affixed on the [ceiling] walls and floor around the gallery windows. Installed in rhythmic patterns, the overall form of the postcards was read as a giant wave crashing through the panoramic windows.”2 Tremblay’s use of the ocean as a borrowed view enabled the viewer to become enveloped in color and form, and the White Box that comprised the rest of the gallery space enhanced the perceived motion of the wave as a constant ebb and flow. The Lost Wave illustrates the progression of Camouflage from Minimalist installations that extruded into a space, encroaching the physical boundaries of viewers, to its more modern relevance as a two-dimensional material application that envelops the viewer.

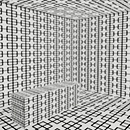

The feeling of disconcertment that O’Brien attributes to Camouflage is present in resort and spa interiors, as well, but in a less severe manner. The lobby of the Morgans Hotel (1984) by Andrée Putman in New York City depicts a similar optical illusion to cubic forms utilized by Andrea Palladio in his 15th century Santo Spirito, Venice.3 The eye dances along the floor in an attempt to discern a flat plane from a visually uneven surface that is not conducive to forward motion. As Putman applies the pattern solely to the floor, the lobby is not an encompassing example of Camouflage; however, her usage of the Palladian pattern suggests a successive appreciation of Camouflage in hospitality design.

In contemporary iterations, repeated patterns are demure, often wrapping only a small portion of the interior, such as in the Four Seasons Resort (1999) in Punta Mita, Mexico, or Fabio Novembre’s Una Hotel Vittoria (2003) in Florence, Italy, where the spatial confusion is brief and visually and physically adjacent to a more traditionally treated room. The material wrapping of these spaces is meant to to transport the guest to an otherworldly zone of relaxation, a disconnection from daily stresses. An example of this is present in a hotel in Oslo, Norway, that combats the constant cold with a Camouflage application in each guestroom, as “the color of the ceiling is always carried down one of the walls, and the color of the floor is taken up on the opposite wall, resulting in a cozy “wrapping” effect.”4

Designer Fabio Novembre’s use of square tesserae for the Una Hotel Vittoria spa add texture and subtle depth to the vertical and horizontal planes being wrapped, and enable irregular surfaces to be Camouflaged, such as sink basins, soffits, and columns. O’Brien speculated that “[w]hile Camouflage is a relatively rare material application it may become more prevalent as designers continue to explore the effects of patterns and graphics on interior space.”5

A prolific supplier of Camouflage is the Italian company, Bisazza Mosaic whose abstracted graphics have inspired various designers to employ Camouflage in their resort and spa interiors.

end notes

- 1) Elizabeth O’Brien, “Material Archetypes: Contemporary Interior Design and Theory Study” (MA Thesis, Cornell University, 2006), 132.

- 2) "The Lost Wave" [1984] Daniel Tremblay, San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art in Anne Farrell, ed., Blurring the Boundaries: Installation Art 1969-1996 (San Diego: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1997), 98, 99.

- 3) Inlaid marble floors, Santo Spirito Church [15th century] Andrea Palladio; Venice in Richard Weston, Materials, Form and Architecture (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2003), 57.

- 4) Kimberly Bradley, ed., Design Hotels Yearbook 08 (Berlin: Design Hotels AG, 2008), 329; Guest Suite, Four Seasons Resort [1999] Anderson Miller; Punta Minta, Mexico in Peter Vitale, “Goldkey Finalists: Suite,” Interior Design 77, no. 12 (Oct. 2006): 204.

- 5) Lobby, Una Hotel Vittoria [2003] Fabio Novembre; Florence, Italy in Yael Pincus, Ultimate Hotel Design (Barcelona: LOFT Publications, 2004), 350.

- 6) Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Camouflage in resort and spa was developed from the following sources: 2000 Locker Room, Side Hotel [2001] Matteo Thun; Hamburg, Germany in www.bisazza.com (accessed August 20, 2008); Lobby, Una Hotel Vittoria [2003] Fabio Novembre, Architect; Florence, Italy in Paco Asensio, ed. Ultimate Hotel Design (Barcelona: LOFT Publications, 2004), 350; PhotoCrd: Yael Pincus Photography; Lounge, Loisium [2005] Steven Holl Architects; Langenlois, Austria in Margherita Spiluttini, Relax: Interiors for Human Wellness (Boston: FRAME Publishers, 2007), 8-10; PhotoCrd: Christian Richters and Margherita Spiluttini; Lounge, Lanserhof [2006] Regina Dahmen-Ingenhoven; Lans, Austria in Relax: Interiors for Human Wellness, 15,17; PhotoCrd: Studio Holger Knauf.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) Goldfarb, Rachel. “Theory Studies: Archetypical Practices of Contemporary Resort and Spa Design.” M.A. thesis, Cornell University, 2008, 111-118.